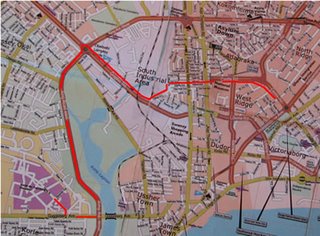

Samuel knew the way, I stared out the window at passing shops and street vendors. One was selling little plastic hooks that can be placed in bathrooms. Another had an assortment of gardening shears and trowels arrayed as a fan on a rectangular board that he displayed, Vanna White style. I purchased a couple of locally produced chocolate bars for 10,000 cedis (9000 = $1) and shared one with Samuel.

At Korle-Bu we headed for radiology, and then searched for a place to park. A uniformed policeman on motorcycle roared up behind us, siren blaring and lights flashing, waving at us angrily to clear the road. A small sedan sped past, surrounded by three other motorcycle police, and pulled with a screech into the radiology parking area in front of us.

"The President's wife is here," explained the doctor inside, apologetically. "If you wouldn't mind, could you come back in perhaps 40 minutes?" I tried to think of something I might do for just 40 minutes, other than wait and stare at the walls of the MRI waiting room.

"What if I come back toward the end of the day," I suggested.

"Of course, come at 6pm, we'll hold the clinic open for you."

"What time do you normally close?"

"Well, 6pm, but we normally keep the doors open until the last patient is served. When you come, just pay the cashier. It will cost 4 million cedis. We charge 2 million for Ghanaians, 4 million for foreigners. I hope you don't mind."

While the first trip out in the early afternoon took about 20 minutes, the early evening trip during rush hour took nearly an hour. I snoozed. Samuel drove, happy to have the overtime pay that evening. We arrived at 5:30.

"The cashier has gone," explained a clerk, "but we can do the MRI for you, and then you can pay when you collect the results."

I agreed and took my seat in the waiting area just outside the MRI room. About five minutes later an attendant took me to a small room, about 2 yards square, roughly the size of a small toilet really, adorned with a single chair. "Please put this on," said the attendant, handing me a hospital gown, "removing all your clothes except your underwear. No metal is allowed in the MRI room. We will take you in soon."

The room was cool from the residual air conditioning from the main waiting area, but after about 10 minutes with the door closed, it became uncomfortably sticky and warm. There was no ventilation. A bright fluorescent bulb glared down at me. There was a tiny window near the ceiling looking out onto a wall of the next building. I could see twilight sky. The window was closed and locked.

After about 15 minutes I arranged my gown and pulled a report from my bag. It was a 50-pager, full of complicated tables and graphs. I finished it.

Around 7pm I opened the door of my cell and peeked outside. The cool air was refreshing. The waiting area was empty but for the attendant.

"Is there any problem?" I inquired.

"No sir, no problem," she politely answered.

"Well, I've been in this little room now for about an hour. It's actually quite warm in here. Do you have any idea when the doctor will be ready to see me?"

"No idea."

I reflected for an instant, and nodded, pulling the door to my cell closed and returning to my chair. I had no more reports to read. The sky visible through my cell window twinkled with stars. I was due to practice with a singing group at 7:30. I'd had no food but for a bit of chocolate since 2pm.

I pulled on my trousers and shirt, and was putting on my socks when suddenly there was a knock and the door opened. Another attendant peered at me in surprise.

"The doctor said 'Ten minutes more'. Please remove your clothes and wait."

"Well," I replied with consternation, "I've had my clothes off now for more than one hour, and I prefer to wear them now." Cheeky, I know, but I was annoyed.

"No, please wait. Only ten minutes."

"No, thank you. And you can close the door now while I continue dressing." The attendant retreated.

I once priced an MRI in the USA for a simple knee exam like mine at $4000. My insurance company refused to authorize it, saying I should instead immobilize the knee for a few months and take cortizone shots. I declined their alternative, and have been living with a bit of pain ever since, which flares up anytime I try anything that involves impact, like jogging.

As MRI's in Ghana are about $500, the equipment is new, and the technicians quite competent, I'll return to Korle-Bu another day.

Try this SoundPrint audio article from Joy FM in Accra about Korle-Bu Teaching Hospital. The link opens up to a description of the story, with a further link to the audio file, which requires RealAudio to play.